[In the aftermath of the siege and shootout at Lindt cafe, thousands of Australians have taken to the streets and to the internet with messages of tolerance. The slogan 'I'll ride with you' has been widely used by Aussies who don't believe that their country's Muslim community should be punished for the actions of Man Haron Monis. Leaders of the Christian, Jewish and Muslim communities have come together to preach peace.

Here in New Zealand, though, some observers have had a very different reaction to the tragedy in Sydney. On a number of right-wing blogs, commenters have made Man Haron Monis into a representative of all Muslims, and have demanded the collective punishment of Australasia's Muslim community.

Here are some excerpts from a long and depressing argument I had in a comments thread at Kiwiblog, the very popular site run by National Party pollster David Farrar, during the Sydney siege. The anti-Muslim ranters at Kiwiblog included David Garrett, a former member of parliament for the Act Party. Garrett is no longer an active member of Act, but his opinions about Muslims are shared by Stephen Berry, who got one of the party's top list spots in this year's elections.]

tranquil wrote:

I would love to see the Australian people rise up against Islam as a result of this incident (but it probably won’t happen). I am fed up with Western people being on the receiving end of such savages and barbarians. I would love to see the tables turned and *Muslims* suffer for once. At least the Buddhists in Burma have the right idea in how they are dealing with the Muslims there.

rightoverlabour:

Would the jihadists who read this blog and downtick the comments please tell us who you are so we can put some bullets in you. Else Eff off to Syria and become martyrs. If it’s just lefty pinko liberal types, please eff off to Syria to go and talk nicely to them. David, Can you track who downticks what? This information could be useful in sanitizing New Zealand from Jihadists…

Odakyu-sen:

Little by little, the notion of stopping and reversing Islamic immigration will gain traction. Actions such as these in Sydney will prompt people to question the standard liberal ideology of the belief in tolerance or non-discrimination. Ask a white blood cell about “tolerance” when it comes across a pathogen in the human body.

Scott wrote:

I’ve noticed the 'stopping and reversing of Islamic immigration' being proposed by people on the right, but these folks never explain how it would be done. It seems to me that such a policy would be impossible to implement without the creation of something akin to a police state here.

Odakyu-sen:

Stopping new immigration is easy. Reversing the trend will involve discrimination. Reclassify Islam as a political belief system. Identify the most virulent strain of Islam (as they are not all the same) and revoke the citizenships of members of that group. Pick one group at a time. Work through the process politely and professionally. Review progress. Proceed on to the next group if required.

Scott wrote:

You want to 'reclassify Islam as a political belief system'. How do you define this system? Is anyone who self-identifies as a Muslim a Muslim? Would you deport members of the Ahmaddiya faith from New Zealand? They first arrived in numbers in the ’70s, have their own prophet and idiosyncratic beliefs, and are detested by jihadis because their liberalism and ecumenism. Indeed, the Ahmaddiya have often been the target for Al Qaeda attacks. Sectarian Middle Eastern governments persecute the Ahmaddiya, accusing them of apostasy. You'd be sending some of these people to their deaths.

Religious communities which use the Koran and uphold Mohammed as a prophet but do not consider themselves Muslims would also presumably have to dealt with. The Baha’i community reveres Mohammed, but also regards the Torah and the New Testament as part of the word of God. Presumably our Baha’i Kiwis would have to reform their theology, and part company with their Korans, if they wanted to stay in their homes...

The policy you're proposing would require the constant monitoring of immigrant populations, to ensure that Muslims hadn’t slipped into the country by pretending to have another or no religion. Muslim New Zealanders who’d renounced their faith so as to remain in the country would have to watched, in case they showed the same backsliding ways as English recusants in the Elizabethan era. Many Muslims would go underground rather than convert or leave the country; their safehouses would have to be raided and emptied. A branch of the police would have to be organised to sniff out and destroy samizdat editions of the Koran.

What would you do with the Kiwi Muslims who lack dual citizenship? What about our Maori Muslims? Perhaps you think some cash-strapped nation could be persuaded to accept some of the Muslims we expel as refugees, in the same way that Nauru and the Papua New Guinea have accepted asylum seekers spurned by Australia?

waikatosinger wrote:

We don’t need to keep out all Muslims. It is probably enough to ensure we don’t import a large enough number from one place that they can become a community. That is easily achievable by simply setting very small immigration quotas for Muslim countries.

Scott wrote:

The first significant group of Muslim migrants to New Zealand came from Fiji, which is not a Muslim majority country. More recently, many Muslims have arrived from India, which is not a Muslim majority country.

In many places it is difficult to determine the demographic relationship between Muslims and other groups. Are Muslims a majority in Albania, where fifty years of Stalinist rule left most people with little relationship to religion? What about Bosnia, where being Muslim is often a matter of culture rather than going to a mosque? And in many Third World nations it is difficult to get reliable data on the relationship between different religious communities.

Odakyu-sen wrote:

I agree that facing off against “Islam the monolith” will not work. You have to clearly break down “Islam” into the various sects and deal with each one individually. The different sects are, as you point out, not all the same. Like I said: discriminate. Use common sense. Take the initiative.

Scott wrote:

But no matter how much you subdivide the Muslim community – whether you decide to deport everyone who calls themselves a Muslim or just X or Y branch of the religion – you are going to face the same logistical problems. Let’s say you decide to pick on Sunni Islam, and leave alone Shi’a and other branches of the faith. You still have the problem of constantly monitoring the New Zealand population for Sunni texts, for secret prayer meetings, for signs of evangelising. You still have to hunt underground Sunni believers through safehouses and encrypted internet sites. You still have to maintain a constant watch for ‘self-converts’ – and since there’s nothing so glamorous as a banned ideology you’ll get a stream of these. You still have to maintain prisons where suspected Sunni are held and interrogated, and deportation camps where the condemned await exile.

And you can’t do all these things without creating a police state.

waikatosinger wrote:

I do believe in religious freedom. Don’t you?

I do believe in religious freedom. Don’t you?

Scott wrote:

I hope it’s clear that I’ve been trying to call the bluff of those who demand that Islam be banned from New Zealand. I think that by examining the logistics of any attempt to ban Islam we can show what a terrible move it would be.

The only religion ever to be banned in New Zealand is indigenous. For fifty-five years, Maori were barred by law from worshipping their gods and consulting their tohunga...

The Tohunga Suppression Act was motivated by hysteria and punished a whole religious community for the alleged misdeeds of one of its members. It’s a part of our history which we should remember when we hear calls for the banning of Islam and the deportation of Muslims.

David Garrett wrote:

It appears to be an invariable rule: Let Muslims get to 2% of the population (2.5% in Australia apparently) and you get problems…let them get to 5% (as in the UK) and ghettoization and atrocities occur…It seems the jihadis in Australia aren’t waiting until they get to 5%…

As for the bullshit that banning further immigration from Islamic countries would mean we had a police state here, what a total and unmitigated load of crap…Very very simple: a change of policy to allow no immigration at all from specified countries…easy peasy…

Any country in the Middle East (even Israel, there are Arabs there too) plus any other country which is officially Islamic – such as Pakistan – and any whose citizens have been involved in terrorism… I don’t give a rats how many countries that is…Call it racist if you like – I really don’t care – but can anyone really argue that illiterate uneducated Somalis add anything to our society…except risk??

Scott wrote:

According to David Garrett, we should prevent a Muslim demographic bomb from exploding in New Zealand by banning migration ‘from any country in the Middle East’, plus any other country that is ‘officially Islamic’.

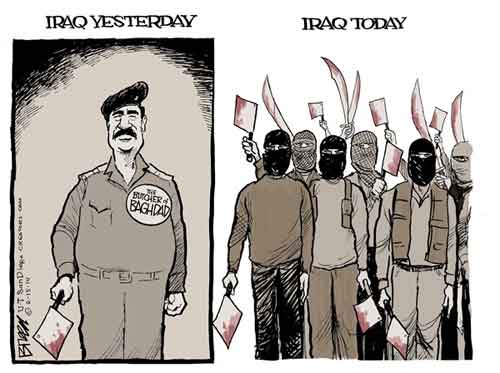

As someone pointed out upthread, though, many of the migrants that have arrived in New Zealand from Middle Eastern nations are not even Muslim, let alone supporters of groups like ISIS and Al Qaeda. Many of the Iraqis who live here, for instance, are members of religious minorities – Chaldeans, other Christians, Mendaens. Another big chunk of the Iraqi migrant population are Kurdish Muslims. These communities have arrived here because they have been displaced from their homes by Bush’s war and by the various religious fundamentalists that have taken power in its wake. It is hard to think of any New Zealanders who would be less inclined to raise the black flag of ISIS and Al Qaeda.

The example of New Zealand's Iraqi community shows why bigoted generalisations shouldn’t be allowed to guide immigration policy.

[Posted by Scott Hamilton]